Babylon (meaning "Confusion"), formally known as Babel, was (1) a Mesopotamian city, and (2) an ancient Empire (See Ancient Babylon).

City location[]

Babylon was located along the Euphrates River on the Plains of Shinar approximately 870 km (540 mi) E of Jerusalem and some 80 km (50 mi) S of Baghdad. The ruins of Babylon extend over a vast area in the form of a triangle. Several mounds are scattered over the area. Tell Babil (Mujelibe), in the northern part of the triangle, preserves the ancient name and is located about 10 km (6 mi) N of Hilla, Iraq.[1]

Fortification[]

Schematic showing Babylon on the Euphrates River with major areas within inner and outer walls.

The city lay on both sides of the Euphrates River. A double system of walls surrounded Babylon, making it seemingly impregnable. The inner rampart, constructed of crude bricks, consisted of two walls. The inner wall was 6.5 m (21.5 ft) thick. The outer wall, situated 7 m (23 ft) away, was about 3.5 m (11.5 ft) thick. These walls were buttressed by defense towers, which also served to reinforce the walls structurally. About 20 m (66 ft) outside the outer wall was a quay made of burnt brick set in bitumen. Outside this wall was a moat connected with the Euphrates to the N and S of the city. It provided both water supply and protection against enemy armies. Babylonian documents indicate that eight gates gave access to the interior of the city. So far, four of Babylon’s gates have been discovered and excavated.[1]

Defense[]

The outer rampart E of the Euphrates was added by Nebuchadnezzar II (who destroyed Solomon’s temple), thus enclosing a large area of the plain to the N, E, and S for the people living nearby to flee to in case of war. This outer rampart also consisted of two walls. The inner wall, made of unbaked bricks, was about 7 m (23 ft) thick and was buttressed with defense towers. Beyond this, about 12 m (40 ft) away, was the outer wall of baked bricks, made in two parts that were interlocked by their towers: one was almost 8 m (26 ft) thick, and the adjoining part was about 3.5 m (11.5 ft) thick. Nabonidus joined the ends of the outer rampart by constructing a wall along the eastern bank of the river. This wall was about 8.5 m (28 ft) wide and also had towers as well as a quay 3.5 m (11.5 ft) wide.[1]

Herodotus, Greek historian of the fifth century BCE, says that the Euphrates River was flanked on either side with a continuous quay, which was separated from the city proper by walls having gateways. According to him, the city walls were about 90 m (295 ft) high, 26.5 m (87 ft) thick, and about 95 km (59 mi) long. However, it appears that Herodotus exaggerated the facts regarding Babylon. Archaeological evidence shows that Babylon was much smaller in size, with the outer rampart much shorter in length and height. No evidence has been found to verify the existence of a quay lining the immediate western bank of the river.[1]

Processional Way[]

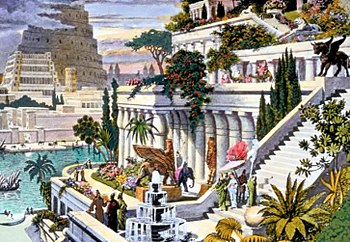

Hand-coloured engraving, probably made in the 19th century after the first excavations in the Assyrian capitals, depicts the fabled Hanging Gardens, with the Tower of Babel in the background.

Streets ran through the city from the gates in the massive walls. The Processional Way, the main boulevard, was paved and the walls alongside it were decorated with lions. Nebuchadnezzar II repaired and enlarged the old palace and built a summer palace some 2 km (1.5 mi) to the north. He also built a great structure of vaulted archways, tier upon tier, known as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and famed as a “wonder of the ancient world.”[1]

Original tiles of the processional street.

World trade center[]

The metropolis, astride the watercourse of the Euphrates, was a commercial and industrial center of world trade. More than an important manufacturing center, it was a commercial depot for trade between the peoples of the East and the West, both by land and by sea. Thus her fleet had access to the Persian Gulf and the seas far beyond.[1]

Religion[]

Impression of the cylinder seal of Ḫašḫamer, ensi (governor) of Iškun-Sin c. 2100 BC. The seated figure is probably king Ur-Nammu, bestowing the governorship on Ḫašḫamer, who is led before him by a lamma (protective goddess). Sin/Nanna himself is indicated in the form of a crescent

Babylon was a religious place. Evidence from excavations and from ancient texts points to the existence of more than 50 temples. The principal god of the imperial city was Marduk, called Merodach in the Bible. It has been suggested that Nimrod was deified as Marduk, but the opinions of scholars as to identifications of gods with specific humans vary. Triads of deities were also prominent in the Babylonian religion. One of these, made up of two gods and a goddess, was Sin (the moon-god), Shamash (the sun-god), and Ishtar; these were said to be the rulers of the zodiac. And still another triad was composed of the devils Labartu, Labasu, and Akhkhazu. The Babylonians believed in the immortality of the human soul.[2]

The Babylonians developed astrology in an effort to discover man’s future in the stars. Magic, sorcery, and astrology played a prominent part in their religion. Many celestial bodies were named after Babylonian gods. Divination continued to be a basic component of Babylonian religion in the days of Nebuchadnezzar.[1]

Biblical history[]

Babylonian territory upon Hammurabi's ascension in 1792 BCE to his death in 1750 BCE

The Hebrew Bible is often consulted to help reconstruct early events of Babylon's history. Nimrod is thought to have lived in the latter part of the third millennium BCE, and is attributed to having founded Babylon, the capital of man’s first political empire. Construction of this city, however, suddenly came to a halt when confusion in communication occurred (Gen 11:9). Later generations of rebuilders came and went. Hammurabi enlarged the city, strengthened it, and made it the capital of the Babylonian Empire under Semitic rule.[1]

Cuneiform cylinder from reign of Nebuchadnezzar II honoring the exorcism and reconstruction of the ziggurat Etemenanki by Nabopolassar.

Under the control of the Assyrian World Power, Babylon figured in various struggles and revolts. Then with the decline of the second world empire, the Chaldean Nabopolassar founded a new dynasty in Babylon about 645 BCE. His son Nebuchadnezzar II, who completed the restoration and brought the city to its greatest glory, boasted, “Is not this Babylon the Great, that I myself have built?” (Da 4:30) In such glory it continued as the capital of the third world power until the night of October 5, 539 BCE. (Gregorian calendar), when Babylon fell before the invading Medo-Persian armies under the command of Cyrus the Great.[1]

That fateful night in the city of Babylon, Belshazzar held a banquet with a thousand of his grandees. Nabonidus was not there to see the ominous writing on the plaster wall: “MENE, MENE, TEKEL and PARSIN” (Da 5:5-28). After suffering defeat at the hands of the Persians, Nabonidus had taken refuge in the city of Borsippa to the SW. But Yahweh’s prophet Daniel was on hand in Babylon on that night of October 5, 539 BCE, and he made known the significance of what was written on the wall. The men of Cyrus’ army were not sleeping in their encampment around Babylon’s seemingly impregnable walls. For them it was a night of great activity. In brilliant strategy Cyrus’ army engineers diverted the Euphrates River from its course through the city of Babylon. Then down the riverbed the Persians moved, up over the riverbanks, to take the city by surprise through the gates along the quay. Quickly passing through the streets, killing all who resisted, they captured the palace and put Belshazzar to death. It was all over. In one night Babylon had fallen, ending centuries of Semitic supremacy; control of Babylon became Aryan, and Yahweh’s word of prophecy was fulfilled (Isa 44:27; 45:1, 2; Jer 50:38; 51:30-32).[1]

Fall of Babylon[]

"Entry of Alexander into Babylon", a 1665 painting by Charles LeBrun, depicts Alexander the Great's uncontested entry into the city of Babylon, envisioned with pre-existing Hellenistic architecture.

From 539 BCE, Babylon’s glory began to fade as the city declined. Twice it revolted against the Persian emperor Darius I (Hystaspis), and on the second occasion it was dismantled. A partially restored city rebelled against Xerxes I and was plundered. Alexander the Great intended to make Babylon his capital, but he suddenly died in 323 BCE. Nicator conquered the city in 312 BCE. and transported much of its material to the banks of the Tigris for use in building his new capital of Seleucia. However, the city and a settlement of Jews remained in early Christian times, giving the apostle Peter possible reason to visit Babylon (1Pe 5:13). Inscriptions found there show that Babylon’s temple of Bel existed as late as 75 CE. By the fourth century CE. the city was in ruins, and eventually passed out of existence.[1]

Present day[]

A partial view of the ruins of Babylon from Saddam Hussein's Summer Palace

The city no longer remains, with ruins of the city. The book Archaeology and Old Testament Study states: “These extensive ruins, of which, despite Koldewey’s work, only a small proportion has been excavated, have during past centuries been extensively plundered for building materials. Partly in consequence of this, much of the surface now presents an appearance of such chaotic disorder that it is strongly evocative of the prophecies of Isa. xiii. 19–22 and Jer. l. 39 f., the impression of desolation being further heightened by the aridity which marks a large part of the area of the ruins.”[3]